The first thing I noticed here was the hairstyles. Specifically that they are the same, roughly. I think the doll may have two braids and the girl may have done a braid with more strands, but they both have pretty much the same hairstyle. That is the end of similarities. Their facial expressions are opposites of each other. The doll looks a lot like the one in the book, and the girl could very easily be the actress that played Pecola. Pecola wanted to be like white girls, and the only thing you can really copy without needing money is hair. Clothes aren’t free, jewelery isn’t free, and houses aren’t free, but hair is free. I wouldn’t be surprised if Pecola in the novel copied the hairstyles f white girls at her school as best she could. Almost any single feature on the doll will be the opposite of the same feature on the girl. the doll has very small lips, while the girls lips aer full, for example. The doll looks happy and a little surprised with her eyebrows drawn so high, while the girl looks sullen. The similarity in the hair of the doll and the girl in this picture draw attention to the differences between the doll and the girl.

Image study Leave a comment

Image study Leave a comment

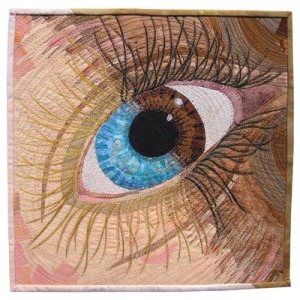

This is a quilt. The artist started by using Photoshop to pu t together a photo of her own daughter with a classmate. When I first saw this, I though it was a painting, because I saw it very small. Full-sized, it is easier to tell that it is a quilt. Both girls had black eyelashes in the photograph,

but in the quilt the artist gave the white girl blonde eyelashes. This is because the image in the book wasn’t of just a girl with blue eyes, but almost always a young blonde girl with pale, pale skin and very, very blue eyes. The blondness is important here to help make the distinction between the two sides of the quilt, and it is easier to draw the line between the two girls.

In the iris, there seems to be more blue than brown, but not by much. This gave me the image of the blue sweeping over the brown as it may have done for Pecola in her mind. At the border between the two girls, on the quilt, the two colors mix together, and there isn’t a straight line between them, but a moving, wavy one. The blue part of the iris does overlap into the other half of the quilt, the one inspired by the black classmate. This, if inspired by something other than The Bluest Eye, probably wouldn’t have been done. However, Pecola did sort of get her eyes changed at the end of the book, so it makes sense that the brown eye would be changing. The two people represented on this quilt are the standard of beauty in the book and Pecola.

http://wwwbluemoonriver.blogspot.com/2007/07/bluest-eye-featured-in-quilting-arts_30.html

Pecola with blue eyes Leave a comment

This chapter is mostly dialogue between Pecola and her imaginary companion. The friend (whose gender I don’t know, so I’m going to say ‘it’ as opposed to he/she). It teases her for looking int he mirror too much, and Pecola accuses it of being jealous. It convinces her to go play outside, and she brags that she can look right at the sun without blinking. Pecola says that her mother doesn’t look right at her because she’s jealous of her blue eyes. She says it’s the same for most everybody she knows. Pecola tells it that she doesn’t go to school because people are prejudiced on account of her new eyes. Pecola asks how blue her eyes are compared to several girls in her school, and it tells her eyes are the bluest of all the girls she knows. When Pecola asks it some personal-type questions, it doesn’t answer, and it offers a weak explanation for why Mrs. Breedlove, and everyone else for that matter, don’t notice it. It mentions Cholly, but Pecola denies that he made her do anything. It turns out Cholly also raped Pecola another time when she was reading on the couch, but her mother didn’t believe her the first time, so she never bothered to tell. We also learn that Sammy’s gone, but not why or how or where. The conversation returns to comparing Pecolas blue eyes to other things, and it reassures her that her eyes are bluer than anything she mentions. Pecola wonders if someone else in the world has bluer eyes than her, and asks it to look at everyones eyes. It tells her she’s being silly and leaves. The perspective switches to Claudia, and she describes Pecola wandering around, flapping her arms, trying ti fly. Claudia and Freida feel they failed since the flowers didn’t bloom and Pecolas baby was born too early and died. Cholly dies in a workhouse, Sammy moves away, and Mrs. Breedlove and Pecola move to a house on the edge of town. Claudia says that Cholly must’ve loved Pecola, but “love is never any better than the lover.” Claudia tals about how she can blame herself and she can blame the earth and she can blame anything, but it doesn’t matter, because it is “much too late.”

Pecola finally got blue eyes, but she lost her mind. She doesn’t see more clearly, she’s just insane. She has no idea what’s happening around her. She doesn’t seem to realize that she was pregnant, just blames everything on jealousy. She is in her own world, in her mind, and there she has blue eyes. Even in her own world, she still worries her eyes aren’t blue enough, and that someone else has bluer eyes. Her friend tells her she has the bluest eyes, but it is a made up friend. She still hasn’t managed to escape Cholly, either. The blue eyes didn’t do what she though they would.

Selling Marigolds Leave a comment

In this short chapter, Claudia and Frieda are going door-to-door selling marigolds to earn money for a new bike. When they go into houses for cold drinks, they listen to adult gossip and piece together the story about Pecola. They learn that Pecolas father got her pregnant than ran away. The adults are disgusted with Cholly and say that Pecola should be taken out of school, and they say that she is also to blame. They also say the baby will be so ugly it is better off dead. The girls feel embarrassed, hurt, and sorry for Pecola, and it upsets them more that none of the adults do. Claudia wants someone to think the black baby can be beautiful, and she thinks this will somehow end the love a white baby-dolls. The girls don’t understand how babies are made in the first place, so they don’t share the disgust of the adults. The girls decide to pray for the baby to live and to mae a sacrifice of the money they earned and the rest of the seed. The bury the money at Pecolas house so they won’t be tempted to get it back out and plant the seed in their own yard to watch over it.

Even though they hear the story about Pecola from the adults perspective only, Claudia resists it. The adults dismiss the entire family as insane, but Claudia tells herself a different story with a beautiful baby. The girls tell themselves that they can save the baby. Their innocence helps them to believe this, since they don’t understand that the health of the baby doesn’t depend on them, and that the chances of the baby living are very low since Pecola is so young and Cholly is the father. They plant the seeds later, hoping that the seeds with grow alongside the baby, and that their sacrifice made a miracle. They also think that the song can help the baby to be healthy.

Soaphead Church Leave a comment

This chapter tells Soaphead Church’s story, whose given name is Elihue Micah Whitcomb. He is a light-skinned West Indian. His family members always try to marry light-skinned people, and they marry each other if they have to. His father was a schoolmaster and his mother was half chinese and died after he was born. He married a woman named Velma who left him two months later. He tried priesthood, the being a caseworker, finally deciding on being a “reader, advisor, and interpreter of dreams.” He studied, took different jobs, and ended up at Lorain, where he rents a back room. the dog there disgusts him, so he buys poison to kill it, but won’t go near it. One day, Pecola comes in to ask him to give her blue eyes. He lies to her and tells her that she will have blue eyes if she gives meat to the dog. The meat had been poisoned, so that the dog would die without Soaphead having to go near it. Pecola runs away when the dog dies. Soaphead writes a letter to god, in which he reveals that he still feels rejected by Velma, and that he is a pedophile. He brags that he granted Pecolas wish, since she will think she has blue eyes and that is just the same as having them. After he writes the letter, he looks at some his favorite trinkets and forgets that he was looking for sealing wax for his letter, and soon after falls asleep.

Soaphead convinces himself that his light skin makes him so superior that he can work miracles and that god is jealous of him. With Pauline and Cholly, the reader feels sympathy when they tell their stories, but with Soaphead the reader just sees him as more ridiculous than they previously thought. It doesn’t help that Soaphead considers his behavior acceptable because he knows the word misanthrope from his education. He cherry-picks from his literature, ignoring the parts that don’t agree with him. Soaphead is religious and believes in god, but is not loving. He only uses god to wish for a better life.

Cholly Breedlove Leave a comment

This chapter describes Cholly, and his childhood. His mother abandons him on a trash heap when he is four days old, but his Great Aunt Jimmy rescues him. She beats his mother and his mother runs away. He learns his father’s name, Samson Fuller, and two years later takes a job Tyson’s Feed and Grain store, where he meets a man named Blue Jack. Blue Jack is kind to Cholly, so that he remembers for a long time. Aunt Jimmy gets sick, and a local healer prescribes pot liquor. She begins to improve, but then she eats a peach cobbler and dies. Cholly doesn’t feel grief when he first finds her, because of the excitement of the funeral and the care everyone is showing him. That day, he gets a girl he likes to take a walk with him, and they end up having sex. A pair of white hunters find them, and decide to watch. The hunters leave when they hear their dogs howling. Later, Cholly fears that Darlene might be pregnant, so he runs away using some money Aunt Jimmy had hidden. He finds his father, but he is disappointed, since Samson assumes that some other woman has sent him and curses him away. He continues his life without caring about whether or how he lives or dies. He only marries Pauline because of her innocence, but marriage makes him feel trapped. This is when he begins to drink. The chapter ends caught up to the present, when Cholly comes home drunk and rapes Pecola, driven by a mixture of tenderness and anger, both coming from guilt. Pecola faints and wakes up under a quilt with her mother standing over her.

This chapter doesn’t give nearly as much sympathy to Cholly as the last one did to Pauline. All through the book, we knew that Cholly was going to get Pecola pregnant, so there was little his story could do to make him more likable, since the reader had plenty of time to hate him for his actions.

Aunt Jimmy represents elderly black women, who have experienced racism and abuse, but also motherhood, and now they have a special freedom. Cholly finds a dangerous freedom after meeting his father, but the one Aunt Jimmy had didn’t lead to an even more dangerous depression and fearlessness like Cholly’s did.

Mrs. (Pauline) Breedlove Leave a comment

This chapter tells the story of Paulines life from childhood. When she was two, she stepped on a nail and was left with a limp. This small disability isolated her from her family. In her isolation, she entertained herself with numbers. She was ‘enchanted’ with numbers and ‘depressed’ by words. Later, her family moves to Kentucky and she is put in charge of caring for the house and her two younger siblings, chicken and pie. Once she turns fifteen, she starts wanting to leave. She falls in love with Cholly, marries him, and moves to Ohio. There, the other women are unfriendly to her, and they mae fun of her walk. She wants clothes like the other women wear, and they start fighting about money. Cholly then starts drinking. Pauline then takes a job as a housekeeper to a wealthy family who has bad habits. One day Cholly shows up to the house drunk demanding money, and Pauline left the job. Her employer refused to hire her back unless she left Cholly, which of course Pauline refuses to do, and they can;t pay the gas bill. The marriage improves when Pauline finds out that she’s pregnant, but she still feels lonely. She watches a lot of movies, which is where she gets her ideas about beauty. While eating candy at the movies, she loses her already infected front tooth, and her attempts to look like a movie star were shot. She feels ugly, and Cholly and her start fighting again. When she is giving birth, a doctor tells a group of students that childbirth isn’t painful for her, “just like a horse.” She loves her baby, but she knows she is ugly. Pauline thinks of herself as a martyr, and after a while of working a lot for a white family, she starts neglecting her own family. Sometimes she remembers when she and Cholly were happier, but now she doesn’t even lie down next to him much because of his drunken smell.

In the previous chapter, it was easy to dislike Pauline because of the way she treated Pecola, but now our opinion of her is tangled up with her past. This chapter helps the reader to see her as someone with bad circumstances who still partially chose her own fate. With some of the story told in Paulines perspective, we can more easily feel for her. It is easy to feel sympathy when she describes how she feels toward the racism that has been directed at her all her life, alone with her bad foot and an abusive husband. Even though she was given bad circumstances, she still made some choices for herself. She accepted her isolation and blamed her foot instead of being more friendly, and she only accepted Cholly because he fit the story she was telling herself about someone coming and taking her away, but without this fantasy she might have seen that they weren’t good for each other.

Spring, Section 1 Leave a comment

When spring arrives, Claudia spends a long time laying in the grass. When she gets home, she finds Frieda crying, and finds out Mr. Henry touched Frieda’s breasts, and was chased away by her parents. Frieda worries about being ruined like the prostitutes, and the girls think they stay skinny by drinking whiskey. When they fo to Pecolas house to see if she can get them some, since Cholly is always drunk, no one is home. The Maginot Line told them Pecola was with her mother at work, so they decide to walk there. They arrive at a beautiful neighborhood whose playground is for white children only, and they are told by Mr.s Breedlove that they can wait for Pecola and walk home with her. Inside the house, a little white girl calls for Polly, which makes Claudia angry since even Pecola calls her mother ‘Mrs. Breedlove.’ Pecola accidentally knock over a fresh pie, burning herself and earning a beating from her mother. Mrs. Breedlove furiously sends the girls away and comforts the little girl who lives at the house.

Frieda is ignorant and confused at her experience, but sexuality was forced upon her by an adult. She depends on her parents reactions to understand what happened. The girls also understand that the Maginot Line is ‘ruined’ but not why, and why her mother is repulsed to her. They guess that it is because she is fat, which is what they don’t lie about her. They also guess that the other two prostitutes ar skinny because they drink whisky, which is something they learned from their mother. They decide that the only way to keep Frieda from being ruined is to keep her skinny, which can be done by drinking whiskey. This shows an entire chain of mistaken reasoning, based on their mothers gossip. However, this situation is very different from Pecola’s, because Friedas parents were quick to protect her, while Cholly did just the opposite to Pecola.

The ‘white’ neighborhood emphasises the connection between race and class. Inside the house the racial connections continue, with the little white girls dressed neatly and delicately, while Pecola is covered in hot berry juice, connecting whiteness with cleanliness. Mrs. Breedlove recognizes that her race is not respected when she slaps Pecola into the pie juice and cleans off the little white girls instead of checking Pecola’s burn. When asked who the girls were, Mrs. Breedlove avoids answering, thus saying Pecola is her daughter. By doing this and staying to make another pie, Mrs. Breedlove chooses her employers over her family.

Geraldine (and the women like her) Leave a comment

5

That’s how many pages were used to describe this type of woman, but no specific name was used until after five pages of description. Basically, she (not one woman, but a type of woman) is very pretty and she comes from a small and pretty town where everyone is employed and probably housed. She takes good care of herself, and she accepts that a black woman during this time is supposed to serve white people, so she goes to a school to learn how and does both with politeness. She never has a boyfriend, but ends up marrying a man who will take of himself and his family. She bears a child, “easily and painlessly.” Up until this point, the description has been positive, but it also makes a point to say that she is not quite average, and not quite above-average. it says “their voices are clear and steady, [yet] they ar never picked to solo.” There is a paragraph that describes her as wanting to be more average. She fights down a ‘funk,’ “the funkiness of passion…nature…[and] the wide range of human emotions.” They avoid loud laughter, sloppy speech, over-gesturing, lips too full, and frizzy hair.

With “what they (their potential husbands) do not know is that this plain brown girl…” the description turns negative, or at least not positive. She is a too strict with her home. She does not enjoy sex. She doesn’t love her family as much as she loves the cat, which is as neat and quiet as she is. She caresses and cuddles the cat in a way that she refuses to caress or cuddle her family.

Specifically, Geraldine. She married a man named Louis and had a son named Junior, who she took excellent care of, but she still loved the cat more. In response, Junior abused the cat, who survived only because Geraldine stayed home more often than she left. Junior was only allowed to play with white children and ‘colored people,’ who were just neat and quiet black children. Junior often threw gravel and rocks at girls who passed by or anyone who wouldn’t play with him. One day, he noticed Pecola walking through the playground alone, so he decided to mess with her. He told her he had kittens, and she could come see them and even have one. For the following paragraph, we see Pecola’s perspective. She sees two rooms, bit very beautiful, colorful, and neat. Junior threw the cat in her face, and she was scratched. Junior blocked the door when she tried to run out, from the outside, but when she stopped crying to pet the cat, he got angry at it. The ended up killing the cat just before Geraldine returned, and blamed it on Pecola. Geraldine calls her a “nasty little black [girl],” and she leaves just as snow starts falling.

We can learn from Geraldine that although she appears sweet and pretty on the outside, we come to hate her at the end of the chapter because she doesn’t love her son and she curses at Pecola, because she isn’t really all that sweet. Also, even though Geraldine-type women can be successful, they end up willingly serving white people. Everything they do, the cleanliness and orderliness, is to get rid of the ‘funk.’ She hates most black people, including herself, and all poor people. These two things are associated with each other, just like whiteness is associate with cleanliness. Geraldine should hate racism and that racism makes her suppress disorderly parts of herself. She instead puts this hatred on her family, and puts the affection she would have put on them she puts on the cat. Junior hates the cat and his mother for this, and he puts his hatred on Pecola and other children at the playground.

I also noticed that both Pecola and the cat are described as very black and all black, but the cat has blue eyes, and the cat is loved over the people in the household. If Pecola knows that the cat is most loved, this will continue her want for blue eyes, translating into everyone loving her.

Maureen Leave a comment

In this chapter (the first chapter of the Winter section), we are introduced to Maureen. Claudia says that “Frieda and I were bemused, irritated, and fascinated by her.” They felt like they should find a flaw, and they were happy to find out she had a ‘dog tooth’ and had been born with an extra finger on each hand. One day, Maureen decides to walk part of the way home with Freida and Claudia. While the girls take off the extra layers they had on on a surprisingly warm day, they noticed a group of boys harassing Pecola Breedlove, and they had made up a rhyme that taunted her skin color and the rumor that her father sleeps naked. Claudia seems to understand that it doesn’t matter that the boys were black and their fathers “had similarly relaxed habits,” but that really that made the insult worse, since they hated themselves along with Pecola. Frieda runs up and hits one boy on the head, and Claudia quickly joins in to save Pecola, but once Maureen runs up, they decide it wouldn’t be right to beat up these three other girls while she was watching. Maureen is kind to Pecola, which surprises the other two girls, and they start to hate her a little less. Maureen makes an offer to buy ice cream, but she ends up only buying for Pecola, and of course, Claudia and Frieda don’t have any money. While they walk, Maureen asks Pecola if she’d ever seen a naked man, to which she replies no, a little surprised, and she says she wouldn’t want to see her father naked, since that’s dirty. Maureen says she didn’t ask about her father, she asked about anyone, and she doesn’t seem to want to let it go that Pecola said her father, specifically. Claudia jumps at the chance to be angry at Maureen, and they start arguing about whether or not Maureen is boy-crazy. Maureen ends it by calling them black and ugly. The girls shout insults after her until they can no longer see her bright green socks. Pecola, of course, accepts this as true, and Claudia describes Maureens parting words as wise and accurate. At home, Mr. Henry gives the girls money for icecream, but they go to the candy store instead, to avoid Maureen. This brings them home earlier than Mr. Henry expected, and they see that he has invited the prostitutes over, and the girls know their other hates these women. When they ask Mr. Henry about them, he says they are in his bible study group. The girls know he is lying, of course, but decide to not tell their mother because they like Mr. Henry.

Maureen’s presence confirms the assumptions the society in this book make, mainly that whiteness is required for beauty and blackness makes ugliness. Maureen is black, but she is lighter than the other black children in her school, so she is prettier according to their rules. She also much wealthier than the other black children.

(whatever flowers symbolize in this novel, they reapear here. As Maureen runs away from the girls after they argue, she is described as having legs like danelion plants that lost their heads. )

Maureen talks about a movie where a girl rejects her black mother, but regrets it at her mother funeral. Maureens mother has seen the movie four times herself, and Maureen wants to see it next time she can. She clearly enjoys the dramatic story, and it may be a reflection of her relationship with her mother, which would explain why her mother enjoys the movie so much, too. This movie also shows how racism has saturated society so that it can be easily missed but still found in a movie or a milk glass (Shirley Temple cup).

Maureen also talks to the girls about menstruation, babies, and naked men, showing that these children are close to the age where they will start to mature, and soon after become adults. Pecola acts very defensive about her father nakedness, foreshadowing what happens later, namely when she has her fathers baby.